Greta

This transpired at a time when I was still afraid of the dark in the stairwell. The darkness rose from the center of the Earth, spread toward the surface like a web of capillaries, and exited just where the stairwells of tower blocks were. Our block was old, its facade dark-colored, with streaks of green and tiny spangles that gleamed in the sun, that gleamed in the light of the street lamps. The darkness was in league with all the stairwells in the world known to me, which comprised a few streets in town.

The street lamps were special, each one a cluster of three great white orbs on a metal post. Somebody dubbed them mother’s tears, and older boys would make snowballs, press stones into the hearts of them, and with these loaded snowballs, break the tears of the street lamps. The town was full of broken white spheres hanging from curved lamp posts. Although mother’s tears seldom actually came in full complements of three, they shone brightly, especially when they were capped with snow and heralded the arrival of the new year—the smell of exploded firecrackers, the smell of snow in the air, the great excitement of the life ahead.

I developed particular techniques for driving the dark from the stairwell, because at the time there was no electric light in the basement and the dark pushed unstoppably upward, threatening to overcome what little daylight penetrated the cloudy glass of the stairwell door.

Faruk Šehić, trans. Mirza Purić

Women’s War

It’s as though Greta and Nađa were two dispossessed noblewomen. Greta, of course, is a countess, Nađa her right hand. They have now been expelled from their county. Nobody knows them; the faces in the street are strange. None treat them with due respect. In turn, the two of them don’t much care what people in their new town think about them. Greta and Nađa listen to the news, remembering the number of shells that have fallen on such and such town on a given day. They remember the number of dead and wounded, because we all do. It’s an informal sport of sorts, it may become an Olympic discipline someday, and it consists of a radio speaker informing us in a distraught voice that such and such number of howitzer, mortar and cannon shells were fired on town XY during an enemy attack on the very heart of the town. Greta and Nađa are able to tell howitzer and cannon shells from one another, because the former fly a lot longer than the latter and you have time to find cover. They learnt this from our father. At times, radio reports made mention of surface-to-air missiles, which are used – ironically enough – not to shoot down aeroplanes but to destroy our cities and towns. For nothing is the way it may at first seem in war. The missiles have poetic names: Dvina, Neva, Volna. The surface-to-surface missile Luna has the prettiest name. One missile landed near our house, the blast lifted a few tiles off the roof. Dry snow seeped through the hole in the roof onto the concrete steps carpeted with varicoloured rag-rug. The cold falls into our home vertically.

Faruk Šehić, trans. Mirza Purić

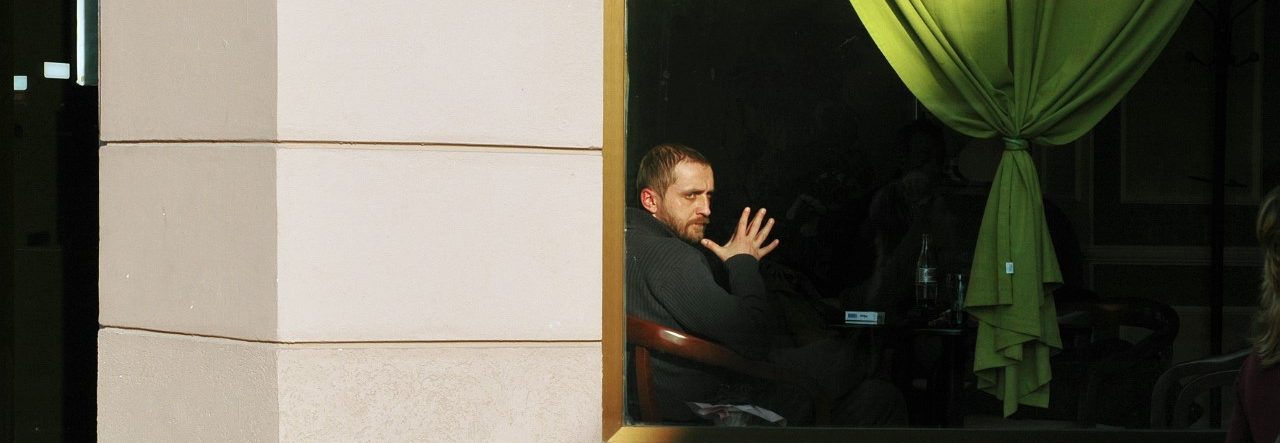

Illustration: Lejla Zjakić

Quiet Flows the Una

Sometimes I’m not me, I’m Gargano. He, that other, is the real me: the one from the shadow, the one from the water. Blue, frail and helpless. Don’t ask me who I am because that scares me. Ask me something else. I can tell you about my memory: about the world of solid matter steadily evaporating and memory becoming the last foundation of my personality, which had almost completely vaporized into a column of steam. When I jump into the past, I’m fully aware of what I’m doing. I want to be whole like most people on this Earth. Now I feel better, staring at the unbroken white line on the steel-blue asphalt. It soothes me. Darkness falls painlessly. I don’t look back. The dark is behind me, but it feels like it’s not there at all; not swallowing up the road, the buildings and the trees. It walks along behind me but dares not come close because it knows that then I would have to use my shield of paper with luminous words, and everything would go down the drain. And no one wants that to happen: neither Gargano, nor the dark, nor that other, meaning me – the astronaut, the adventurer and explorer of rivers and seas.

Fragmenty powieści Książka o Unie, zarejestrowane podczas audycji w Radiu Wrocław Kultura.

Czyta Bartosz Woźny

Faruk Šehić reads an excerpt from Knjiga o Uni (The Book of the Una)

The Pandemonium Diary

24

All cities are now physically distant from one another.

Our reality is like a dynamic universe portrayed as an inflating balloon in the theory of its origin. The more it inflates, the further galaxies move away from each other.

So the cities are moving away from each other.

Cities are galaxies where we’re stuck in our flats and houses. Through the windows, we can see other celestial bodies whizzing past us like we’re two full-speed passing trains on parallel tracks. Whenever we open the windows, a gush of scorchingly hot cosmic air greets us (thrusted from a celestial body sweeping by), while the curfew remains in place outside.